Who was Grandson Sir Otto ?

Grandson [Grandison], Sir Otto de (c.1238–1328), soldier and diplomat, was the eldest son of Pierre de Grandson, lord of Grandson, on the shore of Lake Neuchâtel (now in Switzerland), and his wife, Agnes, daughter of Ulric, count of Neuchâtel. His move away from the family home and into English affairs resulted from his father’s position as the household knight and dependent of Peter of Savoy, earl of Richmond (d. 1268), uncle of Henry III’s queen, Eleanor, and a powerful influence at Henry’s court. Occasionally in England between c.1245 and his death in 1258, Pierre de Grandson was receiving an annual fee of £20 from Henry by 1249/50, and his son Otto was possibly introduced into the household of Edward, Henry’s eldest son and heir, about this time. He first appears, in company with several of Edward’s retainers, in October 1265, when he received a grant of confiscated property in London, and by 1268 he was certainly one of Edward’s knights. He rapidly became one of the prince’s closest friends, accompanying him on his crusade of 1270–72 and appearing as one of his executors in the will that Edward made at Acre in June 1272 [see also Lord Edward’s crusade]. When he returned to England as king in 1274 Grandson emerged as ‘one of Edward’s most trusted henchmen’ (Prestwich, 54).

Henceforth Grandson’s considerable services to the crown were partly military but mainly diplomatic. He fought as a banneret in the first Welsh war of 1277–8, visited Gascony and Paris on Edward’s business in 1278–9, and fought again in the second Welsh war of 1282–3. In March 1284, after its conclusion, he was made justifier of north Wales. Grandson was essentially viceroy of the newly conquered lands, a position suggestive of the confidence placed in him by Edward; and he may have had some influence, as his Savoyard friends and kinsmen certainly did, on the design of the castles by which Wales was to be held down. In 1286 he joined Edward in Gascony, after an embassy to the papal curia, and in 1289–90 he journeyed once again to the curia to discuss, inter alia, the granting of a papal dispensation for the marriage of Edward of Caernarfon, Edward’s son, to Margaret of Scotland (the Maid of Norway), and Edward’s projected crusade.

Although Edward never again went on crusade, Grandson himself led a small expedition to the east in 1290 and was present at the fall of Acre in May 1291. He may have been the author of a memorandum written between 1289 and 1307 concerning plans for a new crusade. After the débâcle at Acre he retired to Cyprus, whence he visited Armenia and Jerusalem before returning to Grandson and finally to England in 1296. His involvement in the Anglo-Scottish war, then just beginning, followed the pattern of his earlier work for Edward. He was present at the surrender of Dunbar on 28 April 1296, which marked the victorious conclusion of Edward’s first campaign, but his main work continued to be high-level diplomacy. He was active in building up Edward’s anti-French coalition in the Low Countries in 1296–7, negotiated for a truce with France in 1298, attended the papal curia in 1300–01, helped to settle the terms for a final French peace in 1303, and was among those sent again to the curia by Edward in 1305 to seek the suspension of Robert Winchelsey (d. 1313), archbishop of Canterbury.

Grandson was rewarded by Edward with extensive land grants in England, especially in Kent, and also in Ireland, and in 1275 with the wardenship of the Channel Islands, later transformed into a life grant. This last proved a source of constant conflict and friction with the islanders. After Edward I’s death in 1307 he left England forever, returning to his ancestral home at Grandson. Although he was occasionally called out of retirement to represent English interests at the curia and at the French court, his main interests were now religious. He took the cross again in 1307, and was a notable benefactor to the Franciscans and Carthusians of his homeland. He died in April 1328 and was buried in Lausanne Cathedral. John Grandison, bishop of Exeter (1328–69), was his nephew. It is hard to think of any comparable figure in medieval English history who lived so long, travelled so widely, or had a career so diverse and adventurous.

How he gets connected to Templar’s?

He went on a second Crusade to the Holy Land in 1290. At the time of the fall of Acre (1291), he was the master of the English knights in Palestine. At Acre he saved the life of fellow Savoyard Jean I de Grailly, with whom he had served Edward in Gascony earlier. After the fall of the city he fled to Cyprus a poor man, but went on a subsequent pilgrimage to Jerusalem. In 1298 or 1299, Otto, Jacques de Moly of the Templars, and Guillaume de Villaret of the Hospitallers campaigned in Cilicia in order to fight off an invasion by the Mamluks. In his La flor des estoires d’Orient, the Armenian monk Hayton of Corycus mentions his activity on the mainland in Cilicia in 1298–1299: Otto de Grandison and the Masters of the Temple and of the Hospitallers as well as their convents, who were at that time [1298 or 1299] in these regions .

Some researchers are wrote that in the Sicily Otto and Jacque De Moly become good friends, and some are claiming that their friendship become was much more earlier. It is difficult to find relevant proof about this. There are speculations about his good relationships with GM Guillaume de Beaujeu who died is siege of Accra, and Thibaud Gaudinn who become GM after, but also he was one of participants of In Accra where Otto was with his forces. One thing is fact that he left England in 1307 and gone to Swiss in Lausanne. As we know Swiss accepted many KT after 1307, and it is question was the Otto man who have had credit for that, for survival of order, but in different way.

The man who saved the Templar’s true or MYTH??

One very satisfying finding as a result of research of The Templar’s Two Kings and a Pope, my novel about the Knights Templar, was the discovery of Lord Otto de Grandson and the enormity of his accomplishments. He worked in secret to establish the first democracy in Europe in 2,000 years, Switzerland. As it turns out, I wasn’t the first to discover him; the Bundesbrief Society, a group dedicated to Swiss heritage contacted me after I published the novel to tell me that they had been researching Otto as well, and agreed with my findings. Be that as it may, I’m still very gratified to have found him on my own and to publicize what he did.

Discovering the Templars’ Master Spy

I became intrigued with Lord Otto de Grandson early on during my research. Once I confirmed what the Templars’ Gnostic secret society, The Brotherhood, had accomplished in their covert war against the French king Philip IV, to keep him from taking over the Holy Roman Empire, mostly through the English, I knew that someone near England’s Edward I had to be a member of The Brotherhood. It was just a matter of identifying key suspects and tracking their movements to see whether they were in the right place at the right time; and of course, any hints as to their motivation and character. Lord Otto de Grandson quickly stood out: a seemingly loyal subject, the king’s key diplomat in his dealings with the French crown. When I discovered that he had made a special trip to Acre as it fell to the Turks, he became my key candidate, for I knew that this was probably the time when The Brotherhood secured their cherished “Holy Grail,” the only plausible reason why a 53-year old key English official, who also happened to be a high-ranking Brotherhood member, was doing battle in the Holy Land while his precious talents were sorely needed back home. He had already “Taken up the Cross” (gone on Crusade) with Edward years before, so his duty to the Church had been satisfied. When I found out that he was a Swiss (that is the cantons that would soon form the republic), I knew I had found my man. When I graphed key events that had to do with the formation of Switzerland with Otto’s life, there was no doubt. He alone was responsible for everything that led to that notorious emancipation, a radical new paradigm in governance that did away with monarchy.

Otto’s Plan: A Quest

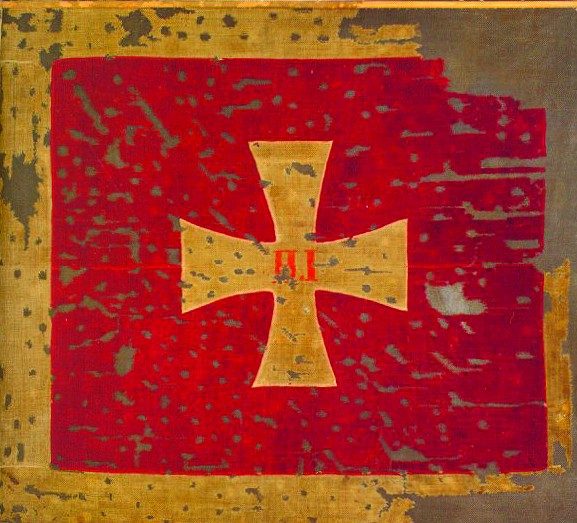

One key indicator that Otto had a secret master plan was the timing of a critical event. Not long after the Templar’s were arrested on orders from the pope and they ceased their invaluable financial operations, Switzerland was open for business, providing the same services. Centuries later historians found that a key number of Templar’s had moved to Switzerland with their financial know-how at the right moment. I discovered evidence that the Templars had also helped by training and possibly leading the local peasants to fight against the Austrians. It’s no coincidence that Switzerland’s flag consists of a Templar cross (all four legs the same size) against a red background.

When I put together the other pieces, how Flanders was used to distract and weaken the French, the tug of war in Scotland, the evident assassination of key French officials and ultimately very likely Philip IV; it all pointed to the workings of The Brotherhood, and specifically Lord Otto de Grandson, whose ultimate target was the Holy Roman Empire, which at the time was relatively weak and disorganized. It was very important for Otto and his cohorts to keep it that way. If the French king became Emperor, all of Otto’s plans would forever dissipate as the Empire became unified with the most powerful and highly organized monarchy in Europe. All of this is the subject of my novel, and how everything came to a head in 1315 after a long and secret war against the French king in which Otto successfully maneuvered the Templars, the English, the Scots, the Flemish and ultimately the French, for his own ends. In the process he saved the Templar Order from being destroyed by the French king. The events that he had set in motion eventually led the Brotherhood’s leadership no other option but to escape en mass to Scotland and Switzerland.

Otto was a very astute, energetic, highly intelligent man who used every skill and talent at his disposal to free his homeland. But how did he manage to end up in England in such a position of power?

Otto’s Journey to England’s Court

Otto was a small child when his father went to work for the English crown. This seems very unusual for someone to come from so far away, an obscure forest canton (a district) within the Holy Roman Empire’s territory and under the jurisdiction of the Duchy of Austria. Otto’s family was very well off; they were land barons in the area of Lake Neuchatel and the town of Grandson (Great Sound).

What would motivate a wealthy land baron in Switzerland to go to work for the English crown, a long and perilous journey to a foreign and remote land, and why would he take his infant son? Why not his entire family?

The answer can be found in the deceivingly sudden and successful emancipation of the forest cantons from the Holy Roman Empire one generation later. It would seem that Otto’s father was already connected to The Brotherhood, and that he was perhaps one of several “plants” in key European courts, plausibly even the papacy. A father would pass on his mission to his son, waiting for the right opportunity to act. This Swiss Master Plan evidently took much planning and very elaborate, patient, and methodical implementation, an almost impossible undertaking that succeeded thanks to Otto.

Otto was the same age as the future Edward I, and they became fast childhood friends (a plausible reason for his being brought along by his father). They studied, played, and were knighted together; when they grew up Otto became Edward’s confidant and faithful aide. He was right beside his king when he went on Crusade and on the various campaigns, including Wales. He saved his king’s life, at least once, when Edward was struck with a poisoned arrow during the Crusade and Otto sucked the poison out. In due time, Edward bestowed lands to his loyal friend, but Otto never moved away from the court. When hostilities started against France, Otto made himself indispensable as the king’s chief diplomat.

All the while Otto was working in secret within The Brotherhood, maneuvering the Templars to contain the French king in Aquitaine, developing a rebel uprising in Flanders against Philip and training the peasant army in the forest cantons. Following the successful conclusion of his efforts, Otto retired to his castle in Switzerland where he lived peacefully until his death at the ripe old age of 90.

Sources:

Sir Otho de Grandison 1238?-1328, Girart Dorens, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society

http://www.templars.org.uk/public/history/p_history_6_glossary.htm